Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology

Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Background, Anatomy, Pathophysiology

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a primary malignancy of the liver and occurs predominantly in patients with underlying chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. The cell(s) of origin are believed to be the hepatic stem cells, although this remains the subject of investigation.Tumors progress with local expansion, intrahepatic spread, and distant metastases.

HCC is now the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, with over 500,000 people affected. The incidence of HCC is highest in Asia and Africa, where the endemic high prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C strongly predisposes to the development of chronic liver disease and subsequent development of HCC.

The presentation of HCC has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Whereas in the past, HCC generally presented at an advanced stage with right-upper-quadrant pain, weight loss, and signs of decompensated liver disease, it is now increasingly recognized at a much earlier stage as a consequence of the routine screening of patients with known cirrhosis, using cross-sectional imaging studies and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) measurements.

The threat of HCC is expected to continue to grow in the coming years.The peak incidence of HCC associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has not yet occurred. There is also a growing problem with cirrhosis, which develops in the setting of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH typically develops in the setting of obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and it will undoubtedly remain a significant problem, given the obesity epidemic occurring in the United States.Thus, developing effective and efficient care for patients with end-stage liver disease and HCC must become a significant focus.

Resection may benefit certain patients, albeit mostly transiently. Many patients are not candidates given the advanced stage of their cancer at diagnosis or their degree of liver disease and, ideally, could be cured by liver transplantation. Globally, only a fraction of all patients have access to transplantation, and, even in the developed world, organ shortage remains a major limiting factor. In these patients, local ablative therapies, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), chemoembolization, and potentially novel chemotherapeutic agents, may extend life and provide palliation.

A complete understanding of the surgical and interventional approach to the liver requires a comprehensive understanding of its anatomy and vascular supply.The liver is the largest internal organ, representing 2-3% of the total body weight in an adult. It occupies the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, surrounding the inferior vena cava, and attaches to the diaphragm and parietal peritoneum by various attachments that are commonly referred to as ligaments.

The vascular supply of the liver includes two sources of inflow that travel in the hepatoduodenal ligament, as follows:

The hepatic artery is generally derived from the celiac axis, which originates on the ventral aorta at the level of the diaphragm. Common variations include a replaced right hepatic artery, which originates from the superior mesenteric artery, a replaced left hepatic artery, which is derived from the left gastric artery, or a completely replaced common hepatic artery, which can originate from the superior mesenteric artery or the aorta. The hepatic artery supplies 30% of the blood flow to the normal liver parenchyma but greater than 90% to hepatic tumors, including both HCC and metastatic lesions.

The other major inflow vessel is the portal vein which carries 70-85% of the blood into the liver. The portal vein is confluence of the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein, which drain the intestines, pancreas, stomach, and spleen.

The primary venous drainage of the liver is through three large hepatic veins that enter the inferior vena cava adjacent to the diaphragm. The right hepatic vein is generally oval in shape, with its long axis in the line of the vena cava. The middle and left hepatic veins enter the inferior vena cava through a single orifice in about 60% of individuals. In addition, there are 10-50 small hepatic veins that drain directly into the vena cava.

The biliary anatomy of the liver generally follows hepatic arterial divisions. The common bile duct gives off the cystic duct and becomes the hepatic duct. The hepatic duct then divides into two or three additional ducts draining the liver. There is significant variation in the biliary anatomy, and thus, careful preoperative imaging is vital before any major hepatic resection.

The vascular anatomy of the liver defines its functional segments. Bismuth synthesized existing knowledge and new insight into the anatomy of the liver.Bismuth defined the right and left hemilivers, which are defined by a line connecting the gallbladder fossa and the inferior vena cava, roughly paralleling the middle hepatic vein that is slightly to the left.

The right hemiliver (lobe) is divided into four segments (ie, 5, 6, 7, 8), each of which is supplied by a branch of the portal vein. The right hemiliver drains via the right hepatic vein. The left hemiliver (lobe) is composed of three segments (ie, 2, 3, 4). Segment 4 is the most medial and is adjacent to the middle hepatic vein. Segments 2 and 3 make up the left lateral section, are to the left of the falciform ligament, and drain via the left hepatic vein. Finally, segment 1 (caudate lobe) is located behind the porta hepatis and adjacent to the vena cava.

In general, resection of the liver is divided into the following two main categories:

Commonly, a right hepatectomy refers to the removal of segments 5-8, an extended right hepatectomy (right trisectionectomy) includes segments 4-8, a left hepatectomy includes segments 2-4, and an extended left hepatectomy (left trisectionectomy) includes segments 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. A left lateral sectionectomy includes only segments 2 and 3. The caudate lobe can be removed as an isolated resection or as a component of one of the more extensive resections noted above. The extent of resection that can be tolerated is based upon the health of the remnant liver.

The pathophysiology of HCC has not been definitively elucidated and is clearly a multifactorial event. In 1981, after Beasley linked hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection to HCC development, the cause of HCC was thought to have been identified.However, subsequent studies failed to identify HBV infection as a major independent risk factor, and it became apparent that most cases of HCC developed in patients with underlying cirrhotic liver disease of various etiologies, including patients with negative markers for HBV infection and who were found to have HBV DNA integrated in the hepatocyte genome.

Inflammation, necrosis, fibrosis, and ongoing regeneration characterize the cirrhotic liver and contribute to HCC development. In patients with HBV, in whom HCC can develop in livers that are not frankly cirrhotic, underlying fibrosis is usually present, with the suggestion of regeneration. By contrast, in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV), HCC invariably presents, more or less, in the setting of cirrhosis. This difference may relate to the fact that HBV is a DNA virus that integrates in the host genome and produces HBV X protein that may play a key regulatory role in HCC development;HCV is an RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm and does not integrate in the host DNA.

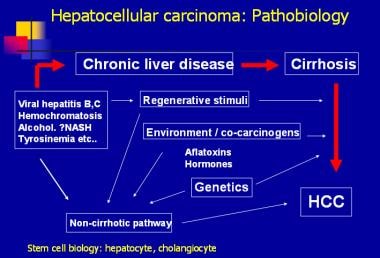

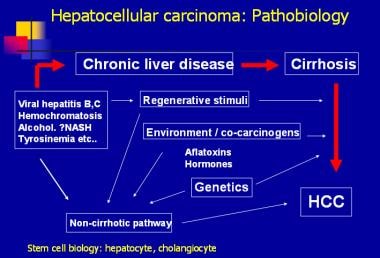

The disease processes, which result in malignant transformation, include a variety of pathways, many of which may be modified by external and environmental factors and eventually lead to genetic changes that delay apoptosis and increase cellular proliferation (see the image below).

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology.

Efforts have been made to elucidate the genetic pathways that are altered during hepatocarcinogenesis.Among the candidate genes involved, the p53, PIKCA, and β-catenin genes appear to be the most frequently mutated in patients with HCC. Additional investigations are needed to identify the signal pathways that are disrupted, leading to uncontrolled division in HCC. Two pathways involved in cellular differentiation (ie, Wnt-β-catenin, Hedgehog) appear to be frequently altered in HCC. Upregulated WNT signaling appears to be associated with preneoplastic adenomas with a higher rate of malignant transformation.

Additionally, studies of inactivated mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in four major subtypes of HCC are being performed. A total of 18.2% of individuals with HCV-associated HCC in the United States and Europe harbored ARID2 inactivation mutations. These findings suggest that ARID2 is a tumor suppressor gene commonly mutated in this tumor subtype.

Whereas various nodules are frequently found in cirrhotic livers, including dysplastic and regenerative nodules, no clear progression from these lesions to HCC occurs. Prospective studies suggest that the presence of small-cell dysplastic nodules conveyed an increased risk of HCC, but large-cell dysplastic nodules were not associated with an increased risk of HCC. Evidence linking small-cell dysplastic nodules to HCC includes the presence of conserved proliferation markers and the presence of nodule-in-nodule on pathologic evaluation. This term describes the presence of a focus of HCC in a larger nodule of small dysplastic cells.

Some investigators have speculated that HCC develops from hepatic stem cells that proliferate in response to chronic regeneration caused by viral injury.The cells in small dysplastic nodules appear to carry markers consistent with progenitor or stem cells.

In the United States, HCC, with its link to the hepatitis C epidemic, represents the fastest growing cause of cancer mortality overall and the second fastest growing cause of cancer deaths among women, according to data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program.

Over the past 20 years, the incidence of HCC has more than doubled, from 2.6 to 5.2 per 100,000 population. Among African Americans, the increase has been even greater (ie, from 4.7 to 7.5 per 100,000 population overall and to 13.1 per 100,000 population among males). Mortality has similarly increased from 2.8 to 4.7 per 100,000 population over the past decade alone.

Worldwide, the incidence of HCC in developing nations is over twice the incidence of that in developed countries. In 2000, the age-adjusted incidence of HCC in men was 17.43 per 100,000 population in developing countries compared with only 8.7 per 100,000 population in the United States. Among women, the disparity was also significant (6.77 vs 2.86 per 100,000 population). The highest incidence of HCC is in East Asia, with incidence rates in men of 35 per 100,000 population, followed by Africa and the Pacific Islands.

Mortality figures mirror the incidence figures for HCC. In developing countries, the mortality from HCC in men is more than double that in developed countries (16.86 vs 8.07 per 100,000 population). In Asia and Africa, the mortality figures are 33.5 and 23.73 per 100,000 population, respectively.

In the United States, the average age at diagnosis is 65 years; 74% of cases occur in men. The racial distribution includes 48% whites, 15% Hispanics, 14% African Americans, and 24% others (primarily Asians). The incidence of HCC increases with age, peaking at 70-75 years; however, an increasing number of young patients have been affected, as the demographic shifts from primarily alcoholic liver disease to those in the fifth to sixth decades of life as the consequences of viral hepatitis B and C acquired earlier in life and in conjunction with high-risk behavior. The combination of viral hepatitis and alcohol significantly increases the risk of cirrhosis and subsequent HCC.

The major risk factors for developing hepatocellular carcinoma vary by region and degree of national development (see Table 1 below). In the United States, the risk factors have historically included alcoholic cirrhosis, HBV infection, hemochromatosis, and now HCV infection.However, the obesity epidemic has resulted in a growing population of patients with NAFLD (ie, NASH). Patients with NAFLD can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and now HCC.These patients are expected to drive the HCC epidemic in the United States and other developed countries.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer and Estimate of Attributable Fractions (Open Table in a new window)

In the developing world, viral hepatitis (primarily hepatitis B), continues to represent the major risk for the development of HCC. The impact of hepatitis B vaccination on the eventual rate of HCC remains to be determined.The results of the vaccination of newborns are encouraging.

Temporal trends suggest that the epidemic of HCC is likely to continue, reflecting the reservoir of the viral hepatitis endemic in the population. In the United States, the annual incidence of new acute HCV infections appears to have decreased since the mid-1980s. However, the delay between HCV infection and HCC development can be up to 30-40 years, leading to the belief that the epidemic of HCC is unlikely to begin to decrease until 2015-19.

Overall, it is estimated that 1.5% of the US population is infected with HCV, of whom 20-30% may develop cirrhosis. Among patients with cirrhosis, the incidence of HCC is 1-6%. This risk is compounded by concurrent alcohol abuse, which increases the risk of cirrhosis and HCC in patients with viral hepatitis.

Other trends driving the epidemic include the aging population, obesity, and, perhaps, improved survival of patients with cirrhosis through better management of ascites and portal hypertension. The worldwide burden of HCC is also likely to continue. While significant progress has been made worldwide through HBV vaccination as part of the expanded program for vaccination by the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of chronic liver disease remains significant among the older population who is at risk of developing HCC.

Clinical Presentation

Luca Cicalese, MD, FACS Professor of Surgery, John Sealy Distinguished Chair in Transplantation Surgery, Director, Texas Transplant Center and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MSc, MA Vice Chair and Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Gastrointestinal Medicine, and Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine; Director, Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Yale-New Haven Hospital; American Gastroenterological Association Fellow

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MSc, MA is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Physiological Society, American Society of Nephrology, Association for Academic Surgery, International Society of Nephrology, New York Academy of Sciences, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Received royalty from AMGEN for consulting; Received ownership interest from Ardelyx for consulting.

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS Assistant Professor of Surgery, State University of New York Upstate Medical University; Consulting Staff, Director of Surgical Research, Robert Packer Hospital; Associate Program Director, Department of Surgery, Guthrie Clinic

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, Association of Program Directors in Surgery, American Medical Association

Acknowledgements

David A Axelrod, MD, MBA Assistant Professor of Surgery, Section Chief, Solid Organ Transplantation, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center

David A Axelrod, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and New Hampshire Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Dirk J van Leeuwen, MD, PhD Professor of Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School; Consulting Staff, Director of Hepatology, Associate Director, Hepatopancreatico-biliary Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Consulting Gastroenterologist, White River Junction Veterans Administration Medical Center

Dirk J van Leeuwen, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Gastroenterological Association, Dutch Society of Gastroenterology/Enterology, Dutch Society of Hepatology, European Association for the Study of the Liver, and New Hampshire Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

References

Large hepatocellular carcinoma. Image courtesy of Arief Suriawinata, MD, Department of Pathology, Dartmouth Medical School.

Photomicrograph of a liver demonstrating hepatocellular carcinoma. Image courtesy of Arief Suriawinata, MD, Department of Pathology, Dartmouth Medical School.

MRI of a liver with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Ultrasonographic image of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Arterial phase CT scan demonstrating enhancement of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Portal venous phase CT scan demonstrating washout of hepatocellular carcinoma.

The Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) approach to hepatocellular carcinoma management. Adapted from Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J, Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer Group. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. Feb 2004;10(2 Suppl 1):S115-20.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology.

Right hepatectomy. Part 1: Dissection of portal vein. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

Right hepatectomy. Part 2: Devascularization of right liver. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

Right hepatectomy. Part 3: Suturing and dividing. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

Table 1. Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer and Estimate of Attributable Fractions

Table 2. Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) Determination in Liver Disease

Table 3. Patient Survival Rates Following Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a primary malignancy of the liver and occurs predominantly in patients with underlying chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. The cell(s) of origin are believed to be the hepatic stem cells, although this remains the subject of investigation.Tumors progress with local expansion, intrahepatic spread, and distant metastases.

HCC is now the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, with over 500,000 people affected. The incidence of HCC is highest in Asia and Africa, where the endemic high prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C strongly predisposes to the development of chronic liver disease and subsequent development of HCC.

The presentation of HCC has evolved significantly over the past few decades. Whereas in the past, HCC generally presented at an advanced stage with right-upper-quadrant pain, weight loss, and signs of decompensated liver disease, it is now increasingly recognized at a much earlier stage as a consequence of the routine screening of patients with known cirrhosis, using cross-sectional imaging studies and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) measurements.

The threat of HCC is expected to continue to grow in the coming years.The peak incidence of HCC associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has not yet occurred. There is also a growing problem with cirrhosis, which develops in the setting of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH typically develops in the setting of obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and it will undoubtedly remain a significant problem, given the obesity epidemic occurring in the United States.Thus, developing effective and efficient care for patients with end-stage liver disease and HCC must become a significant focus.

Resection may benefit certain patients, albeit mostly transiently. Many patients are not candidates given the advanced stage of their cancer at diagnosis or their degree of liver disease and, ideally, could be cured by liver transplantation. Globally, only a fraction of all patients have access to transplantation, and, even in the developed world, organ shortage remains a major limiting factor. In these patients, local ablative therapies, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), chemoembolization, and potentially novel chemotherapeutic agents, may extend life and provide palliation.

Anatomy

A complete understanding of the surgical and interventional approach to the liver requires a comprehensive understanding of its anatomy and vascular supply.The liver is the largest internal organ, representing 2-3% of the total body weight in an adult. It occupies the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, surrounding the inferior vena cava, and attaches to the diaphragm and parietal peritoneum by various attachments that are commonly referred to as ligaments.

The vascular supply of the liver includes two sources of inflow that travel in the hepatoduodenal ligament, as follows:

- Hepatic artery

- Portal vein

The hepatic artery is generally derived from the celiac axis, which originates on the ventral aorta at the level of the diaphragm. Common variations include a replaced right hepatic artery, which originates from the superior mesenteric artery, a replaced left hepatic artery, which is derived from the left gastric artery, or a completely replaced common hepatic artery, which can originate from the superior mesenteric artery or the aorta. The hepatic artery supplies 30% of the blood flow to the normal liver parenchyma but greater than 90% to hepatic tumors, including both HCC and metastatic lesions.

The other major inflow vessel is the portal vein which carries 70-85% of the blood into the liver. The portal vein is confluence of the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein, which drain the intestines, pancreas, stomach, and spleen.

The primary venous drainage of the liver is through three large hepatic veins that enter the inferior vena cava adjacent to the diaphragm. The right hepatic vein is generally oval in shape, with its long axis in the line of the vena cava. The middle and left hepatic veins enter the inferior vena cava through a single orifice in about 60% of individuals. In addition, there are 10-50 small hepatic veins that drain directly into the vena cava.

The biliary anatomy of the liver generally follows hepatic arterial divisions. The common bile duct gives off the cystic duct and becomes the hepatic duct. The hepatic duct then divides into two or three additional ducts draining the liver. There is significant variation in the biliary anatomy, and thus, careful preoperative imaging is vital before any major hepatic resection.

The vascular anatomy of the liver defines its functional segments. Bismuth synthesized existing knowledge and new insight into the anatomy of the liver.Bismuth defined the right and left hemilivers, which are defined by a line connecting the gallbladder fossa and the inferior vena cava, roughly paralleling the middle hepatic vein that is slightly to the left.

The right hemiliver (lobe) is divided into four segments (ie, 5, 6, 7, 8), each of which is supplied by a branch of the portal vein. The right hemiliver drains via the right hepatic vein. The left hemiliver (lobe) is composed of three segments (ie, 2, 3, 4). Segment 4 is the most medial and is adjacent to the middle hepatic vein. Segments 2 and 3 make up the left lateral section, are to the left of the falciform ligament, and drain via the left hepatic vein. Finally, segment 1 (caudate lobe) is located behind the porta hepatis and adjacent to the vena cava.

In general, resection of the liver is divided into the following two main categories:

- Nonanatomic (wedge) resections are generally limited resections of a small portion of liver, without respect to the vascular supply

- Anatomic resections involve removing one or more of the eight segments of the liver

Commonly, a right hepatectomy refers to the removal of segments 5-8, an extended right hepatectomy (right trisectionectomy) includes segments 4-8, a left hepatectomy includes segments 2-4, and an extended left hepatectomy (left trisectionectomy) includes segments 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. A left lateral sectionectomy includes only segments 2 and 3. The caudate lobe can be removed as an isolated resection or as a component of one of the more extensive resections noted above. The extent of resection that can be tolerated is based upon the health of the remnant liver.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of HCC has not been definitively elucidated and is clearly a multifactorial event. In 1981, after Beasley linked hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection to HCC development, the cause of HCC was thought to have been identified.However, subsequent studies failed to identify HBV infection as a major independent risk factor, and it became apparent that most cases of HCC developed in patients with underlying cirrhotic liver disease of various etiologies, including patients with negative markers for HBV infection and who were found to have HBV DNA integrated in the hepatocyte genome.

Inflammation, necrosis, fibrosis, and ongoing regeneration characterize the cirrhotic liver and contribute to HCC development. In patients with HBV, in whom HCC can develop in livers that are not frankly cirrhotic, underlying fibrosis is usually present, with the suggestion of regeneration. By contrast, in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV), HCC invariably presents, more or less, in the setting of cirrhosis. This difference may relate to the fact that HBV is a DNA virus that integrates in the host genome and produces HBV X protein that may play a key regulatory role in HCC development;HCV is an RNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm and does not integrate in the host DNA.

The disease processes, which result in malignant transformation, include a variety of pathways, many of which may be modified by external and environmental factors and eventually lead to genetic changes that delay apoptosis and increase cellular proliferation (see the image below).

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology. Efforts have been made to elucidate the genetic pathways that are altered during hepatocarcinogenesis.Among the candidate genes involved, the p53, PIKCA, and β-catenin genes appear to be the most frequently mutated in patients with HCC. Additional investigations are needed to identify the signal pathways that are disrupted, leading to uncontrolled division in HCC. Two pathways involved in cellular differentiation (ie, Wnt-β-catenin, Hedgehog) appear to be frequently altered in HCC. Upregulated WNT signaling appears to be associated with preneoplastic adenomas with a higher rate of malignant transformation.

Additionally, studies of inactivated mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in four major subtypes of HCC are being performed. A total of 18.2% of individuals with HCV-associated HCC in the United States and Europe harbored ARID2 inactivation mutations. These findings suggest that ARID2 is a tumor suppressor gene commonly mutated in this tumor subtype.

Whereas various nodules are frequently found in cirrhotic livers, including dysplastic and regenerative nodules, no clear progression from these lesions to HCC occurs. Prospective studies suggest that the presence of small-cell dysplastic nodules conveyed an increased risk of HCC, but large-cell dysplastic nodules were not associated with an increased risk of HCC. Evidence linking small-cell dysplastic nodules to HCC includes the presence of conserved proliferation markers and the presence of nodule-in-nodule on pathologic evaluation. This term describes the presence of a focus of HCC in a larger nodule of small dysplastic cells.

Some investigators have speculated that HCC develops from hepatic stem cells that proliferate in response to chronic regeneration caused by viral injury.The cells in small dysplastic nodules appear to carry markers consistent with progenitor or stem cells.

Epidemiology

In the United States, HCC, with its link to the hepatitis C epidemic, represents the fastest growing cause of cancer mortality overall and the second fastest growing cause of cancer deaths among women, according to data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program.

Over the past 20 years, the incidence of HCC has more than doubled, from 2.6 to 5.2 per 100,000 population. Among African Americans, the increase has been even greater (ie, from 4.7 to 7.5 per 100,000 population overall and to 13.1 per 100,000 population among males). Mortality has similarly increased from 2.8 to 4.7 per 100,000 population over the past decade alone.

Worldwide, the incidence of HCC in developing nations is over twice the incidence of that in developed countries. In 2000, the age-adjusted incidence of HCC in men was 17.43 per 100,000 population in developing countries compared with only 8.7 per 100,000 population in the United States. Among women, the disparity was also significant (6.77 vs 2.86 per 100,000 population). The highest incidence of HCC is in East Asia, with incidence rates in men of 35 per 100,000 population, followed by Africa and the Pacific Islands.

Mortality figures mirror the incidence figures for HCC. In developing countries, the mortality from HCC in men is more than double that in developed countries (16.86 vs 8.07 per 100,000 population). In Asia and Africa, the mortality figures are 33.5 and 23.73 per 100,000 population, respectively.

In the United States, the average age at diagnosis is 65 years; 74% of cases occur in men. The racial distribution includes 48% whites, 15% Hispanics, 14% African Americans, and 24% others (primarily Asians). The incidence of HCC increases with age, peaking at 70-75 years; however, an increasing number of young patients have been affected, as the demographic shifts from primarily alcoholic liver disease to those in the fifth to sixth decades of life as the consequences of viral hepatitis B and C acquired earlier in life and in conjunction with high-risk behavior. The combination of viral hepatitis and alcohol significantly increases the risk of cirrhosis and subsequent HCC.

The major risk factors for developing hepatocellular carcinoma vary by region and degree of national development (see Table 1 below). In the United States, the risk factors have historically included alcoholic cirrhosis, HBV infection, hemochromatosis, and now HCV infection.However, the obesity epidemic has resulted in a growing population of patients with NAFLD (ie, NASH). Patients with NAFLD can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and now HCC.These patients are expected to drive the HCC epidemic in the United States and other developed countries.

Table 1. Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer and Estimate of Attributable Fractions (Open Table in a new window)

| Europe and United States | Japan | Africa and Asia | ||||

| Estimate | Range | Estimate | Range | Estimate | Range | |

| HBV | 22 | 4-58 | 20 | 18-44 | 60 | 40-90 |

| HCV | 60 | 12-72 | 63 | 48-94 | 20 | 9-56 |

| Alcohol | 45 | 8-57 | 20 | 15-33 | - | 11-41 |

| Tobacco | 12 | 0-14 | 40 | 9-51 | 22 | - |

| OCPs | - | 10-50 | - | - | 8 | - |

| Aflatoxin | Limited exposure | Limited exposure | Limited exposure | |||

| Other | < 5 | - | - | - | < 5 | - |

In the developing world, viral hepatitis (primarily hepatitis B), continues to represent the major risk for the development of HCC. The impact of hepatitis B vaccination on the eventual rate of HCC remains to be determined.The results of the vaccination of newborns are encouraging.

Temporal trends suggest that the epidemic of HCC is likely to continue, reflecting the reservoir of the viral hepatitis endemic in the population. In the United States, the annual incidence of new acute HCV infections appears to have decreased since the mid-1980s. However, the delay between HCV infection and HCC development can be up to 30-40 years, leading to the belief that the epidemic of HCC is unlikely to begin to decrease until 2015-19.

Overall, it is estimated that 1.5% of the US population is infected with HCV, of whom 20-30% may develop cirrhosis. Among patients with cirrhosis, the incidence of HCC is 1-6%. This risk is compounded by concurrent alcohol abuse, which increases the risk of cirrhosis and HCC in patients with viral hepatitis.

Other trends driving the epidemic include the aging population, obesity, and, perhaps, improved survival of patients with cirrhosis through better management of ascites and portal hypertension. The worldwide burden of HCC is also likely to continue. While significant progress has been made worldwide through HBV vaccination as part of the expanded program for vaccination by the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of chronic liver disease remains significant among the older population who is at risk of developing HCC.

Clinical Presentation

Luca Cicalese, MD, FACS Professor of Surgery, John Sealy Distinguished Chair in Transplantation Surgery, Director, Texas Transplant Center and Hepatobiliary Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Texas Medical Branch School of Medicine

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MSc, MA Vice Chair and Professor, Department of Surgery, Section of Gastrointestinal Medicine, and Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale University School of Medicine; Director, Surgical Research, Department of Surgery, Yale-New Haven Hospital; American Gastroenterological Association Fellow

John Geibel, MD, DSc, MSc, MA is a member of the following medical societies: American Gastroenterological Association, American Physiological Society, American Society of Nephrology, Association for Academic Surgery, International Society of Nephrology, New York Academy of Sciences, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Received royalty from AMGEN for consulting; Received ownership interest from Ardelyx for consulting.

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS Assistant Professor of Surgery, State University of New York Upstate Medical University; Consulting Staff, Director of Surgical Research, Robert Packer Hospital; Associate Program Director, Department of Surgery, Guthrie Clinic

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, Association of Program Directors in Surgery, American Medical Association

Acknowledgements

David A Axelrod, MD, MBA Assistant Professor of Surgery, Section Chief, Solid Organ Transplantation, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center

David A Axelrod, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, American Society of Transplant Surgeons, and New Hampshire Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Dirk J van Leeuwen, MD, PhD Professor of Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School; Consulting Staff, Director of Hepatology, Associate Director, Hepatopancreatico-biliary Center, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Consulting Gastroenterologist, White River Junction Veterans Administration Medical Center

Dirk J van Leeuwen, MD, PhD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Gastroenterological Association, Dutch Society of Gastroenterology/Enterology, Dutch Society of Hepatology, European Association for the Study of the Liver, and New Hampshire Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

References

- Alison MR. Liver stem cells: implications for hepatocarcinogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2005. 1(3):253-60. [Medline].

- Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004 Feb. 10(2 Suppl 1):S115-20. [Medline].

- Bugianesi E. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and cancer. Clin Liver Dis. 2007 Feb. 11(1):191-207, x-xi. [Medline].

- Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN, et al. Hepatic surgical anatomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2004 Apr. 84(2):413-35, viii. [Medline].

- Elwood D, Pomposelli JJ. Hepatobiliary surgery: lessons learned from live donor hepatectomy. Surg Clin North Am. 2006 Oct. 86(5):1207-17, vii. [Medline].

- Bismuth H. Surgical anatomy and anatomical surgery of the liver. World J Surg. 1982 Jan. 6(1):3-9. [Medline].

- Strasberg SM. Nomenclature of hepatic anatomy and resections: a review of the Brisbane 2000 system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005. 12(5):351-5. [Medline].

- Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus. A prospective study of 22 707 men in Taiwan. Lancet. 1981 Nov 21. 2(8256):1129-33. [Medline].

- Zhang X, Zhang H, Ye L. Effects of hepatitis B virus X protein on the development of liver cancer. J Lab Clin Med. 2006 Feb. 147(2):58-66. [Medline].

- McKillop IH, Moran DM, Jin X, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2006 Nov. 136(1):125-35. [Medline].

- Li M, Zhao H, Zhang X, et al. Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2011 Aug 7. 43(9):828-9. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Cameron RG, Greig PD, Farber E, et al. Small encapsulated hepatocellular carcinoma of the liver. Provisional analysis of pathogenetic mechanisms. Cancer. 1993 Nov 1. 72(9):2550-9. [Medline].

- Alison MR. Liver stem cells: implications for hepatocarcinogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2005. 1(3):253-60. [Medline].

- Seeff LB. Introduction: The burden of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004 Nov. 127(5 Suppl 1):S1-4. [Medline].

- Bosch FX, Ribes J, Diaz M, et al. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004 Nov. 127(5 Suppl 1):S5-S16. [Medline].

- Wong JB, McQuillan GM, McHutchison JG, et al. Estimating future hepatitis C morbidity, mortality, and costs in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2000 Oct. 90(10):1562-9. [Medline].

- Armstrong GL, Alter MJ, McQuillan GM, et al. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology. 2000 Mar. 31(3):777-82. [Medline].

- Gambarin-Gelwan M, Wolf DC, Shapiro R, et al. Sensitivity of commonly available screening tests in detecting hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients undergoing liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Jun. 95(6):1535-8. [Medline].

- Yamashita Y, Mitsuzaki K, Yi T, et al. Small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver damage: prospective comparison of detection with dynamic MR imaging and helical CT of the whole liver. Radiology. 1996 Jul. 200(1):79-84. [Medline].

- de Ledinghen V, Laharie D, Lecesne R, et al. Detection of nodules in liver cirrhosis: spiral computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging? A prospective study of 88 nodules in 34 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002 Feb. 14(2):159-65. [Medline].

- Colli A, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography, spiral CT, magnetic resonance, and alpha-fetoprotein in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006 Mar. 101(3):513-23. [Medline].

- Arguedas MR, Chen VK, Eloubeidi MA, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis: a cost-utility analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Mar. 98(3):679-90. [Medline].

- Kim WR. The use of decision analytic models to inform clinical decision making in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005 May. 9(2):225-34. [Medline].

- van Leeuwen DJ, Shumate CR. Space-occupying lesions of the liver. van Leeuwen DJ, et al, eds. Imaging in Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Disease. London: WB Saunders; 2000.

- Kemmer N, Neff G, Kaiser T, et al. An analysis of the UNOS liver transplant registry: high serum alpha-fetoprotein does not justify an increase in MELD points for suspected hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2006 Oct. 12(10):1519-22. [Medline].

- Saffroy R, Pham P, Reffas M, et al. New perspectives and strategy research biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007. 45(9):1169-79. [Medline].

- Lencioni R, Cioni D, Della Pina C, et al. Imaging diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2005. 25(2):162-70. [Medline].

- Kulik LM, Mulcahy MF, Omary RA, et al. Emerging approaches in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007 Oct. 41(9):839-54. [Medline].

- Broelsch CE, Frilling A, Malago M. Hepatoma--resection or transplantation. Surg Clin North Am. 2004 Apr. 84(2):495-511, x. [Medline].

- Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: Implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2005 Sep. 11(9):1086-92. [Medline].

- Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, et al. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005 Apr. 41(4):707-16. [Medline].

- Kaido T, Mori A, Ogura Y, Hata K, Yoshizawa A, Iida T, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. Surgery. 2011 Sep 21. [Medline].

- Cormier JN, Thomas KT, Chari RS, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006 May. 10(5):761-80. [Medline].

- Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Treatment outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma using chemoembolization in combination with other therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006 Dec. 32(8):594-606. [Medline].

- Llovet JM. Updated treatment approach to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2005 Mar. 40(3):225-35. [Medline].

- Mathurin P, Raynard B, Dharancy S, et al. Meta-analysis: evaluation of adjuvant therapy after curative liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 May 15. 17(10):1247-61. [Medline].

- Salem R, Hunter RD. Yttrium-90 microspheres for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006. 66(2 Suppl):S83-8. [Medline].

- Zhu AX. Systemic therapy of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: how hopeful should we be?. Oncologist. 2006 Jul-Aug. 11(7):790-800. [Medline].

- Gemcitabine-oxaliplatin combo effective in advanced liver cancer. Medscape Medical News. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/771715. Accessed: Oct 15 2012.

- Zaanan A, Williet N, Hebbar M, et al. Gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large multicenter AGEO study. J Hepatol. 2012 Sep 15. [Medline].

- Abou-Alfa GK, Schwartz L, Ricci S, et al. Phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Sep 10. 24(26):4293-300. [Medline].

- Liu L, Cao Y, Chen C, et al. Sorafenib blocks the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, inhibits tumor angiogenesis, and induces tumor cell apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma model PLC/PRF/5. Cancer Res. 2006 Dec 15. 66(24):11851-8. [Medline].

- Llovet J, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Randomized phase III trial of sorafenib versus placebo in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25(suppl 18):LBA1.

- Forner A, Hessheimer AJ, Isabel Real M, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006 Nov. 60(2):89-98. [Medline].

- Mathurin P, Raynard B, Dharancy S, et al. Meta-analysis: evaluation of adjuvant therapy after curative liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003 May 15. 17(10):1247-61. [Medline].

- Sugimachi K, Maehara S, Tanaka S, et al. Repeat hepatectomy is the most useful treatment for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001. 8(5):410-6. [Medline].

- Roayaie S, Obeidat K, Sposito C, Mariani L, Bhoori S, Pellegrinelli A, et al. Resection of hepatocellular cancer = 2 cm: results from two western centers. Hepatology. 2012 May 11. [Medline].

- Busuttil RW, Farmer DG. The surgical treatment of primary hepatobiliary malignancy. Liver Transpl Surg. 1996 Sep. 2(5 Suppl 1):114-30. [Medline].

- Penn I. Hepatic transplantation for primary and metastatic cancers of the liver. Surgery. 1991 Oct. 110(4):726-34; discussion 734-5. [Medline].

- Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996 Mar 14. 334(11):693-9. [Medline].

- Bismuth H, Majno PE, Adam R. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1999. 19(3):311-22. [Medline].

- Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. Intention-to-treat analysis of surgical treatment for early hepatocellular carcinoma: resection versus transplantation. Hepatology. 1999 Dec. 30(6):1434-40. [Medline].

- Jonas S, Herrmann M, Rayes N, et al. Survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis according to the underlying liver disease. Transplant Proc. 2001 Nov-Dec. 33(7-8):3444-5. [Medline].

- Philosophe B, Greig PD, Hemming AW, et al. Surgical management of hepatocellular carcinoma: resection or transplantation?. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998 Jan-Feb. 2(1):21-7. [Medline].

- Molmenti EP, Klintmalm GB. Liver transplantation in association with hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of the International Tumor Registry. Liver Transpl. 2002 Sep. 8(9):736-48. [Medline].

- Testa G, Crippin JS, Netto GJ, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis C: recurrence and disease progression in 300 patients. Liver Transpl. 2000 Sep. 6(5):553-61. [Medline].

- Yao FY, Bass NM, Nikolai B, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of survival according to the intention-to-treat principle and dropout from the waiting list. Liver Transpl. 2002 Oct. 8(10):873-83. [Medline].

- Freeman RB Jr. Transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: The Milan criteria and beyond. Liver Transpl. 2006 Nov. 12(11 Suppl 2):S8-13. [Medline].

- Llovet JM, Vilana R, Bru C, et al. Increased risk of tumor seeding after percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2001 May. 33(5):1124-9. [Medline].

- Lencioni R, Crocetti L. A critical appraisal of the literature on local ablative therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005 May. 9(2):301-14, viii. [Medline].

- Lencioni R, Goletti O, Armillotta N, et al. Radio-frequency thermal ablation of liver metastases with a cooled-tip electrode needle: results of a pilot clinical trial. Eur Radiol. 1998. 8(7):1205-11. [Medline].

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004 Nov. 127(5 Suppl 1):S27-34. [Medline].

- Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, et al. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005 May. 9(2):191-211, v. [Medline].

- Lok AS, Everhart JE, Wright EC, Di Bisceglie AM, Kim HY, Sterling RK, et al. Maintenance peginterferon therapy and other factors associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011 Mar. 140(3):840-9; quiz e12. [Medline]. [Full Text].

- Kim RD, Reed AI, Fujita S, et al. Consensus and controversy in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2007 Jul. 205(1):108-23. [Medline].

- Portolani N, Coniglio A, Ghidoni S, et al. Early and late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Ann Surg. 2006 Feb. 243(2):229-35. [Medline].

- Hytiroglou P, Theise ND, Schwartz M, et al. Macroregenerative nodules in a series of adult cirrhotic liver explants: issues of classification and nomenclature. Hepatology. 1995 Mar. 21(3):703-8. [Medline].

- Axelrod D, Koffron A, Kulik L, Al-Saden P, et al. Living donor liver transplant for malignancy. Transplantation. 2005 Feb 15. 79(3):363-6. [Medline].

- Chang MH, Chen TH, Hsu HM, et al. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma by universal vaccination against hepatitis B virus: the effect and problems. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Nov 1. 11(21):7953-7. [Medline].

- El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004 Feb. 126(2):460-8. [Medline].

- Izzo F, Cremona F, Ruffolo F, Palaia R, Parisi V, Curley SA. Outcome of 67 patients with hepatocellular cancer detected during screening of 1125 patients with chronic hepatitis. Ann Surg. 1998 Apr. 227(4):513-8. [Medline].

- Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003 Feb. 37(2):429-42. [Medline].

- Martin AP, Goldstein RM, Dempster J, et al. Radiofrequency thermal ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplantation--a clinical and histological examination. Clin Transplant. 2006 Nov-Dec. 20(6):695-705. [Medline].

- Roayaie S, Schwartz JD, Sung MW, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplant: patterns and prognosis. Liver Transpl. 2004 Apr. 10(4):534-40. [Medline].

- Roskams T. Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2006 Jun 26. 25(27):3818-22. [Medline].

- Sherman M. Pathogenesis and screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2004 May. 8(2):419-43, viii. [Medline].

- Thorgeirsson SS, Grisham JW. Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2002 Aug. 31(4):339-46. [Medline].

- Trinchet JC, Ganne-Carrie N, Nahon P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 May 7. 13(17):2455-60. [Medline].

- Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, et al. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007 Feb. 27(1):55-76. [Medline].

- Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of the proposed UCSF criteria with the Milan criteria and the Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria. Liver Transpl. 2002 Sep. 8(9):765-74. [Medline].

Large hepatocellular carcinoma. Image courtesy of Arief Suriawinata, MD, Department of Pathology, Dartmouth Medical School.

Photomicrograph of a liver demonstrating hepatocellular carcinoma. Image courtesy of Arief Suriawinata, MD, Department of Pathology, Dartmouth Medical School.

MRI of a liver with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Ultrasonographic image of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Arterial phase CT scan demonstrating enhancement of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Portal venous phase CT scan demonstrating washout of hepatocellular carcinoma.

The Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) approach to hepatocellular carcinoma management. Adapted from Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J, Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer Group. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. Feb 2004;10(2 Suppl 1):S115-20.

Hepatocellular carcinoma: pathobiology.

Right hepatectomy. Part 1: Dissection of portal vein. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

Right hepatectomy. Part 2: Devascularization of right liver. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

Right hepatectomy. Part 3: Suturing and dividing. Courtesy of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, featuring Leslie H. Blumgart, MD. (From Blumgart LH. Video Atlas: Liver, Biliary & Pancreatic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010.)

- Table 1. Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer and Estimate of Attributable Fractions[15]

- Table 2. Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) Determination in Liver Disease[24]

- Table 3. Patient Survival Rates Following Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Table 1. Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer and Estimate of Attributable Fractions

| Europe and United States | Japan | Africa and Asia | ||||

| Estimate | Range | Estimate | Range | Estimate | Range | |

| HBV | 22 | 4-58 | 20 | 18-44 | 60 | 40-90 |

| HCV | 60 | 12-72 | 63 | 48-94 | 20 | 9-56 |

| Alcohol | 45 | 8-57 | 20 | 15-33 | - | 11-41 |

| Tobacco | 12 | 0-14 | 40 | 9-51 | 22 | - |

| OCPs | - | 10-50 | - | - | 8 | - |

| Aflatoxin | Limited exposure | Limited exposure | Limited exposure | |||

| Other | < 5 | - | - | - | < 5 | - |

Table 2. Serum Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) Determination in Liver Disease

| Alpha-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | Interpretation |

| >400-500 | - HCC likely if accompanied by space-occupying solid lesion(s) in cirrhotic liver or levels are rapidly increasing. - Diffusely growing HCC, may be difficult to detect on imaging. - Occasionally in patients with active liver disease (particularly HBV or HCV infection) reflecting inflammation, regeneration, or seroconversion |

| Normal value to <400 | - Frequent: Regeneration/inflammation (usually in patients with elevated transaminases and HCV) - Regeneration after partial hepatectomy - If a space-occupying lesion and transaminases are normal, suspicious for HCC |

| Normal value | Does not exclude HCC (cirrhotic and noncirrhotic liver) |

Table 3. Patient Survival Rates Following Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

| Author (Year) | N | Survival Rate | |

| 1 year | 5 years | ||

| Mazzefero (1996) | 48 | 84% | 74% |

| Bismuth (1999) | 45 | 82% | 74% |

| Llovet (1999) | 79 | 86% | 75% |

| Jonas (2001) | 120 | 90% | 71% |

Source...